Pipemakers

The Story of Pipemaking

Aboriginal Background

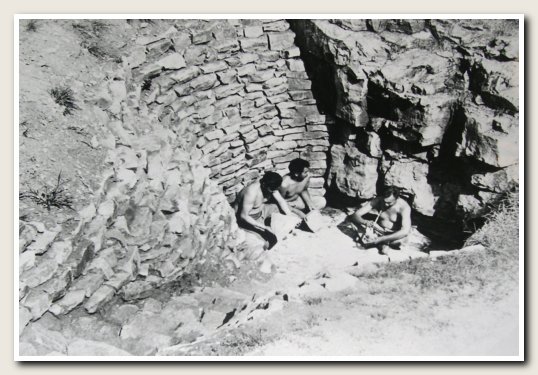

The Indian occupancy of the area and earliest use of catlinite from the quarries has long been discussed, but archeological studies over the past 30 years have greatly improved knowledge in this field.

The proto-Mandan people who once frequented the area are not believed to have used catlinite. The first quarrying here was probably done by people associated with the Oneota Aspect, about 1600 to 1650 A.D. In the earliest historic times these tribes were known as the Iowa and the Oto.

Quite early in historic times the Sioux (or Dakota) moved to the west and southwest. They were better armed than the Iowa and Oto through their trade contacts, but restrained on the north by the Cree and pressed from the northeast by the Chippewa. By about 1700 A.D. the Sioux were in control of the Coteau and remained so until the end of tribal days about a century and half later. Catlinite received its most widespread use during Sioux times.

Early Visitors

The French were trading on the upper Mississippi by the 1690’s, and maintained a number of temporary trading posts within 125 miles of pipestone quarry by 1750. It seems likely that some of their men visited the quarries, but no direct record is available. Territorial Governor Sibley referred to such visits in some of his writings.

Major Taliaferro of the Sioux Agency mentions a visit by unidentified persons to the quarry in 1831 in his Journal. Later that same year, the well-known trader, Philander Prescott, visited the quarry on his way to build a wintering house on the Big Sioux River. Prescott reported that “We arrived at the famous place called the pipestone quarry…We got out a considerable quantity but a good deal of it was shaly and full of seams, so we got only about 20 good pipes after working all day…This quarry was discovered by the Indians but how and when we have never learnt…” He also mentioned his return by way of the quarries in the spring of 1832.

Joseph LaFramboise, a mixed blood trader for the American Fur Company, supposedly quarried pipestone here in 1835 for use in trade.

Most widely publicized and long believed to be “the first white visitor” was George Catlin, who visited the quarries in September 1836. Catlin was the first quarry visitor to “break into print”, and his writings and lectures were popular and widely known. Dr. C.T. Jackson of Boston, to whom Catlin had given samples of stones, originated the term “catlinite,” still applied to the pipestone from these quarries.

Less than 2 years later, Catlin’s friend and host, LaFramboise, guided the first truly scientific expedition to the pipestone quarry. With it the period of Federal contract began.

|

|

|

|

|

Carving Pipes from Stone

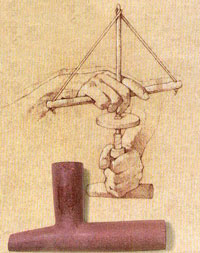

The work of Native American pipecarvers takes many forms. Since the mid-19th century, the inverted T-shaped calumet has been perhaps the shape most recognizable as Plains Indian work. Metal tools acquired from white traders in historic times facilitated more detailed carving, but even in many highly ornate effigy pipes the basic calumet shape is distinct.

Today craftsmen use power saws and drills for speed and precision. Though tools are more sophisticated, the process is similar to that of the age when carving implements were made of stone and wood. These drawings illustrate how calumets might be made without modern technology.

Digging the Pipestone

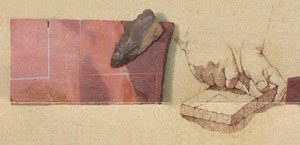

Late summer and fall are the most desirable times to dig, at other times of the year water collects in the pits. After the soil is shoveled away, the top layer of quartzite is broken up carefully with a sledgehammer and wedge to minimize damage to the relatively soft pipestone underneath.

Since the pipestone bed slopes downward to the east, quarries must dig through an increasingly thick layer of quartzite as they quarry new pipestone. Under the quartzite are 1 to 3-inch sheets of catlinite. Quarriers lift the broken sheets from the pits, and then cut them into smaller blocks from which the pipes are carved.

Quarrying here has always been accomplished with respect for the earth and for what it yields. The Sioux traditionally leave an offering of food and tobacco beside the group of boulders known as the Three Maidens in return for this land’s gift of stone.

Making the Stem

Stems are hewn from branches of ash or other hardwood. After rough shaping, the branch is split lengthwise. The pith is scraped from both halves to create a narrow shaft. The halves are rejoined and secured with sap glue and cord. Alternatively, a heated wire is run through the core of a sumac branch to burn out the pith, eliminating the need to split the stem. Traditionally, plainswomen “dressed” the stem by wrapping porcupine quills around part of its length. Paint, carvings, feathers, beads, and even animal heads adorned the stem and signified the pipe’s ceremonial role.

Source: NATIONAL MONUMENT MINNESOTA NATIONAL PARK SERVICE, U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR

Meet Our Pipemakers

Ray Redwing is presently serving on the FSST Executive Committee as Trustee IV. He is serving his second four year term. Ray was first elected in August of 2000. Prior to being elected to serve on the Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe’s Executive Committee, he worked at the Pipestone National Monument for twenty-two seasons as a pipestone pipe carver.

The job was seasonal and lasted from April 1st to October 31st. Ray was one of five to six “artists and demonstrators” that worked two in a work station and carved pipestone into peace pipes, jewelry, arrow heads and Indian designed artifacts.

Ray worked on small jewelry and pieces at first with Chuck and Butch Derby training him on carving pipestone rock and quarrying pipestone from the quarries by the National Monument. He trained under the Derby’s for two years before he was on his own and began designing and carving pipestone pipes with pipe bowls from 4” to 12” in diameter. He became experienced had made fancy pipe bowls with carved buffalo and eagle heads on the front of the bowl.

Ray stated: “I thought it was fun and stress free to work at the National Monument. I could sell my own products to visitors and tourists that came to buy from us artists and demonstrators. People came from all over the nation by car and bus load. I took special orders for pipes from Native American individuals from other tribes, mainly South Dakota and Minnesota, to make traditional T-pipes.” He went on to say: “I like meeting a lot of people from all over, even Europe, they came to the monument and were full of questions and wanted to know about the Native American Culture. Especially the young women and ladies would ask if I still lived in a tee pee, stuff like that.”

According to Redwing, the Pipestone Monument hired one person to do the beadwork on the pipe stem, usually a woman, and 3-6 demonstrators/artists for the carving of pipestone pipes. The demonstrators were placed two in a work station so the tourists and visitors could observe them working with quarried pipestone. Ray said: “Back then, the Monument used to let us work outside, I liked it, and it was a natural setting and nice to work outside. This attracted the visitors driving up to the parking area and they wanted to see what was going on. We quarried our own pipestone. It is wet when it comes out of the ground and you have to wait for it to be dried off before it can be worked with and carved, otherwise our saws and files get jammed up. It is better to work with dry stone and dry dust.”

“A long time ago, the National Monument hired all Native Americans so the tourists could see them. Now there are a few, two in maintenance and one assistant director. I have not carved since I have been elected, I would like to get back into it, it was relaxing and I want to see if I still have it in me,” stated Ray.

Ray was born and raised in Flandreau, attended grade school and high school at Flandreau Public Schools. He is the second oldest of five children. He joined the US Navy right after high school days and served during the Vietnam War Era. Ray has been a member of the Gordon Weston Indian Veterans Lodge/Honor Guard for the past ten years.

Ray also is one of three of the Tribe’s Cultural Preservation Officers and Repatriation Officers, and a member of the Eastern Dakota Treaty Committee. The Eastern Dakota Treaty Committee has representatives from the Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe, Yankton Sioux Tribe, Sisseton Wahpeton Sioux Tribe, Santee Sioux Tribe of Nebraska, Lower Sioux Community-Morton, Minnesota, Upper Sioux Community-Granite Falls, Minnesota, and Canadian Dakota Tribes from Canada.

Trustee IV Ray Redwing is the Executive Committee Liaison for the Law Enforcement Department, Public Safety Commission and the Elderly Program.

Ray feels that repatriation is on going and the need for it to be done is because of the identified remains and artifacts that are Dakotas that are in museums and burial sites that are being excavated at development sites. Ray stated: “Brandon, South Dakota has a huge site they are building homes on and it is located on burial mounds and sites.”